Meeting the Needs of English Learners | Quincy Public Schools

QUINCY – Ile’s first year Rodolfo Rodriguez read aloud to learn more about Chris, Mark and John.

John is bad at making his bed. Mark is worse at making his bed. Chris is the worst at making his bed.

It’s a lesson about words that mean similar things and words that mean more than one – potentially confusing topics for any first grader, but especially for someone who speaks Spanish at home rather than English.

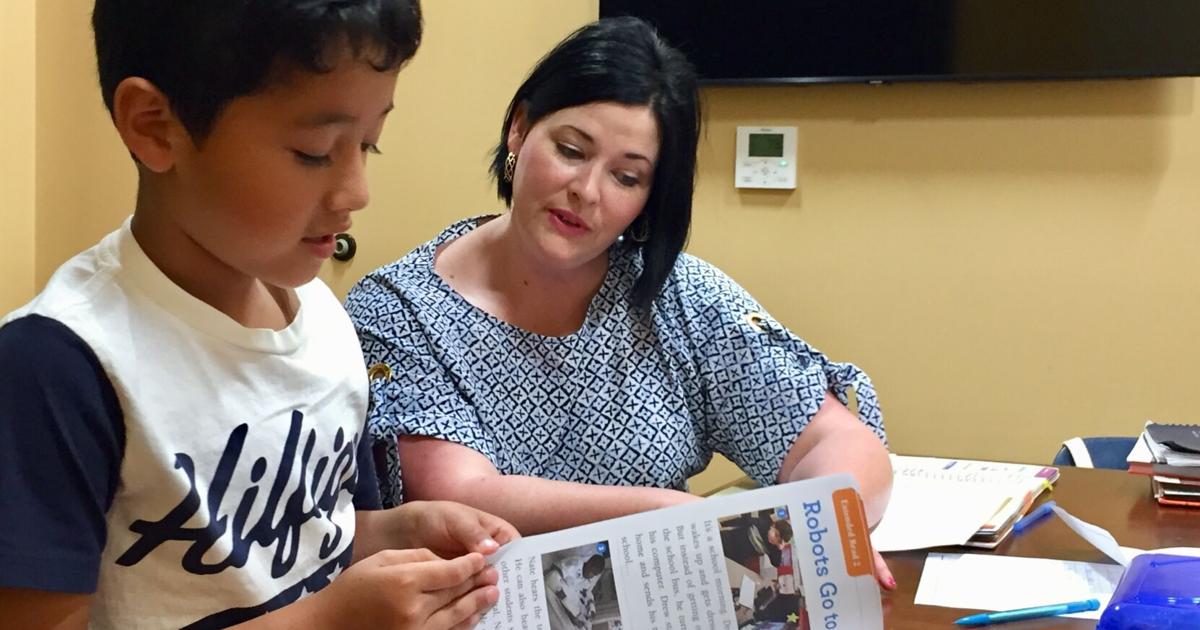

Twice-weekly tutoring sessions with Sara Lepper, offered through Quincy Public Schools’ English Language Learner program, help bridge the language barrier.

“She teaches me more,” said Rodolfo.

It’s hard to learn English “because there are some tricky words that I might not know,” Rodolfo said, but he said it’s a lot easier to speak and understand his second language now than it was last year in kindergarten .

Rodolfo’s teacher, Kathy Womack, who doesn’t speak Spanish, worried about how to communicate with him at the start of the school year.

“He’s the first ELL student I’ve had in my 18 years of teaching,” Womack said.

“His language and his knowledge of how words are put together have improved so much. He really understands things like that more than my kids, who have always spoken English,” she said. “Having that extra layer of support (from Lepper) is very helpful. We can work together to make improvements and see progress in the student’s language.”

Helping students succeed in the classroom is a goal of the school district’s little-known ELL program, which has served 35 students so far this school year, up from 23 in the previous two years, who speak nine languages.

“We’re seeing a slight increase in the number of students coming in and being identified as English learners,” said Kim Dinkheller, director of curriculum, instruction and assessment at QPS. “The other thing we saw is the level of support that is needed for students who come with limited English skills. More and more students are coming in with no knowledge of English.”

When the district’s existing program didn’t meet all the needs of an eighth-grade student who spoke only Italian, Dinkheller began expanding efforts about four years ago, tapping state funds to meet academics and other needs of students — and their families — to support. in building awareness of ELL services.

What the program offers matters to ELL students—and to Quincy.

“As our community becomes more diverse, in the public school we try to meet as many needs as possible,” said Lepper, who teaches nine K-5 ELL students through the program this year. “We must continue to embrace diversity. We can learn a lot from these children.”

The Illinois State Board of Education defines English language learners as all students in preschool through 12th grade whose native language is a language other than English and whose proficiency in speaking, listening, reading, and writing or understanding English is not yet at a level appropriate to the student’s disposal :

- The ability to succeed in classrooms where the language of instruction is English.

- The opportunity to fully participate in school activities.

- Ability to achieve proficiency level in Illinois State assessments.

Prospective ELL students at QPS are identified through a native language survey at enrollment and then go through a state-approved screening process that looks at speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills.

Identified ELL students are connected to Mike McKinley, the QPS ELL Support Liaison, who works to identify the students’ academic and social needs and develop an individual action plan, which is reviewed each year. An annual assessment of English proficiency determines whether the student will continue in the ELL program.

McKinley “is sometimes the first person we introduce a family to. He can translate for them,” said Dinkeller. “He does everything for our families. It not only connects them to services in QPS, but in Quincy itself.”

The needs vary depending on the student.

“Some come to us with a very formal schooling, then we got a student who moved from a very rural part of Mexico and didn’t go to school every day,” Dinkheller said.

Action plans for non-English students may include attempting interaction with the teacher at least once a day. Plans for more fluent students might ask questions to clarify something said in the classroom.

Statistics show that it can take ELL students entering first grade with Level 1 English proficiency up to six years to become proficient. “We put this plan together knowing that they’re not going to make it there in a year,” Dinkheller said.

McKinley connects students with her support team of QPS staff who work to meet academic and socio-emotional needs – often acting as translators for the families.

“They don’t know how to open a bank account here, how to get the services of a pediatrician for their children. I take them to dentist appointments, show them where to shop in town. If they don’t have a family network here, they’re pretty isolated,” McKinley said.

He routinely checks in with the students and families, and rapid Spanish comes out of the phone as he speaks to Oralia Rincon, who has a son and daughter at Lincoln-Douglas and a daughter at QHS, and has moved from Minnesota to Quincy for her husband’s work.

“The more I understand my role, the more I understand that I’m not doing enough of what needs to be done,” he said. “We need time to structure the competent, detailed program that will meet these needs faster and better. We try it. We will get there.”

But there are plenty of bright spots — including seventh-grader Megan Ortiz stopping by McKinley’s room to say hello.

Ortiz moved to Quincy from Mexico last year, spoke little English and relied on a translator on her phone. A very determined student with a very supportive family, McKinley said she excels at her classwork and at speaking her second language.

“What helped me the most was studying on my own,” says Ortiz. “I feel adjusted. I started my own debating club at school. It’s going really well. I feel like I’m making progress. I don’t use the translator much anymore.”

Tutors like Lepper and Zach Bentley, who work with 6-12 students, provide another resource for ELL students.

“My role is really to bridge the gap between the language spoken at home and English,” said Lepper. “I really work on the nuances of our language – understand metaphors, similes, to/two/too – and help them understand our culture too. Parents want their children to be immersed in the culture here in the US, but also to remain true to their former culture.”

Lepper uses the class-level syllabus to work with Rodolfo and fourth-grader Mia Ortiz-Malagon in Iles. “She teaches me new things I didn’t know. I want to work with her more,” Mia said.

“All of the children advanced at least a whole grade this year and are doing their job very, very well,” said Lepper. “The kids have to realize, and I tell them that all the time, they have such a gift. You will become fluent in two languages. That will be one such trait as they get older and move into the workforce.”

At home, Rodolfo becomes a teacher and helps his parents learn English.

“My father and mother cannot speak English. Everyone in my house speaks Spanish, so every time my dad doesn’t know what to say to someone, I tell my dad or mom what to say,” he said.

A translator feature in SeeSaw allows Womack to communicate with Rodolfo’s mother, who does not speak English.

“I send her messages in English but she can see them in Spanish. It helps a lot,” Womack said. “She tries very hard to learn it herself at home through Rodolfo.”

Rodolfo focuses on speaking English rather than Spanish at school, but Womack says his classmates think it’s “really cool” to hear his Spanish.

“It makes her curious,” she says. “They will count to 10 in Spanish to show that I can speak some Spanish too. They think they’re pretty cool if they can say something Rodolfo can say.”

Comments are closed.