The peoples and cultures of Indonesia

Maria Zurbuchen

In the universe of global imagery, Bali shines as one of the brightest stars in the constellation of places considered the closest to paradise on earth. Centuries ago, European traders, soldiers, Orientalists, and colonial administrators began to inscribe a Balinese civilization. They have been followed by Western anthropologists, writers and artists who have celebrated the island’s natural beauty and complex culture, and more recently millions of visitors who have boosted tourism over the past half century. According to the two French authors of this new book, Bali’s legacy today is a colorful mosaic of fluid tradition, shifting identities, mass marketing and encroaching modernism.

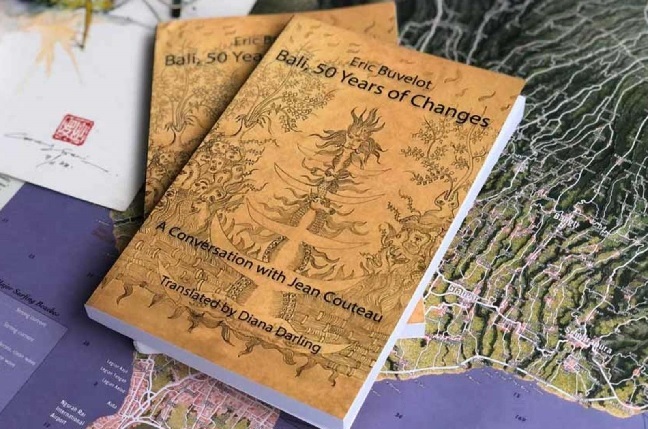

in the Bali: 50 Years of Change: A Conversation with Jean Couteau, Eric Buvelot, and Jean Couteau have drawn a complicated, comprehensive, and controversial picture of Balinese consciousness, social patterns, and religious life, and Bali’s place in the Indonesian national framework. It’s arguably the most ambitious attempt at a holistic view of the island since Fred Eiseman, Jr Bali: Sekala and Niskala (1990) or Adrian Vickers’ Bali: A created paradise (1989). However, this is not a historical narrative or the culmination of years of extensive research on any particular subject. Instead we find a series of transcribed conversations between two emigrants: Buvelot, a journalist who has lived on the island since 1995, and Couteau, a renowned writer, social observer and commentator closely linked to Bali since the 1970s.

Adopting an interview format, Buvelot draws on Couteau’s lived experiences and decades of interaction with Balinese of all backgrounds and fellow Indonesians to weave approximately 20 hours of dialogue into a composite contemporary portrait. Central themes of the book’s 16 chapters are loosely organized along the original Indian philosophical principles of kama (desire), arta (wealth), darma (duty), and moksa (liberation). The two men interact on the site as observers, provocateurs and debaters, each reflecting his position as insider-outsider; “We are part of the sociological object that we analyze,” writes Buvelot.

The resulting dialectic is pervasive and far-reaching, with many unresolved questions and contradictions, reflecting not only the dynamics of systemic change, but also the variable, contradictory, and inherently particularistic configuration of Balinese life in general. Couteau sees power as always negotiated, configured through multiple associations and social ties. While provincial authorities (or previously royal authorities) might seek to enact land use practices or rituals, it is ultimately a local village decision that takes precedence. Centralized power always competes with local power, and what is local is explained by the Balinese in terms of differences, with desa, kala, patra –place, time and pattern. Couteau posits this kind of predictable vagueness as a fundamental strength, stemming from Bali’s heritage of ancestor worship, which underlies religion and social life. The ancestors are local, reincarnated into specific people and places, and both facilitated and constrained the Balinese’s commitment to one another and belonging to the community.

Defining an audience for the book is a mystery as it is aimed neither at the novice, the traveler nor the scholar, and Bali’s expats are a narrow market. Nonetheless, the scope of its subject matter can draw even the casual reader into subjects such as personal morality, environmental pollution, racism, and reincarnation. The rhetorical framework with its four themes is not always successful: themes (e.g. sex, education, urbanization, the violence of 1965) are often dealt with in one chapter and then reappear in another, and there is no index that summarizes the guides readers. The themes ebb and flow through multiple perspectives and revolve around another aspect of something already mentioned under a different heading. This feels frustrating at first, but as I read the book I was reminded of the intricate layering and cyclical structure of gamelan music, building texture through repetition marked at regular intervals by the returning, familiar sound of the gong.

Couteau’s responses to Buvelot’s questions are provoking major changes in Balinese systems, lifestyles and cultural patterns that are both encouraging and disconcerting. Bali thrives on its globally marketed image of green, fertile paddy fields, but today’s society is post-agricultural as many lands have been sold to build roads, shopping malls and resorts, and thousands have moved from village to urban living. Disappearing views and water-based plastic have tarnished the image of pristine nature. While belonging to Indonesia has fostered tolerance of different identities (including foreign ones), universal schooling and modern infrastructure, not to mention investment in a vibrant tourism economy, it has also led to the arrival of economic migrants – sex workers, wage laborers – from other, poorer places, with consequent ethnic tensions and competition. Despite widespread literacy and increased wealth, patriarchy and polygamy continue to disadvantage Balinese women; New norms of gender and sexuality are being flaunted in the tourist areas, but there is resistance in the villages.

Balinese readers in particular may be uncomfortable with some of the harsher glimpses behind the carefully curated image of their ‘Island of the Gods’ as Couteau addresses rape, gigolos and the sexual freedom afforded by motorcycles; disappearance of the natural and architectural heritage; and patterns of violence and public corruption that are all part of contemporary Bali. Buvelot and Couteau could have included more commentary on the emergence of artists, civic groups, social media and NGOs producing counter-narratives to the idealized images of a tourist paradise; While they mention the controversial development project in Benoa, they never fully explain Reklamasi and the reasons why it has sparked widespread opposition.

In the realm of religion, Couteau suggests, Bali’s fundamental core is most challenged. The religion used to focus on the ancestral duties and rituals inherent in families and clans, with an overlay of court-centric ceremonies celebrating Hindu and Buddhist deities, Kawi texts, and Javanese Majapahit lore. Now a growing number of Balinese see themselves as part of the “great global family of Hindus” who are streamlining doctrine and standardizing temple ceremonies under a top-down authority, the Council for Hindu Affairs (Parisada Hindu Darma). This normative thinking is encouraging many Balinese to define themselves as Hindu in new ways, including through the adoption of Sanskrit neologisms and pilgrimages to holy sites in India. Couteau argues that when ethno-religious identity dominates self-awareness, it becomes difficult for Balinese to take a critical stance towards their society; When maintaining the image of “Bali for the World” becomes everyone’s duty, objectivity and reason are lost. Ultimately, he hopes that primordial and ingrained village systems, steeped in ancestral worship, will anchor Balinese identity no matter how strong the winds of change.

Two peculiarities of this book deserve to be emphasized. One is Balinese author Kadek Krishna Adidharma’s revealing foreword, in which he welcomes the two men examining “our idiosyncrasies and contradictions” and acknowledges that although “a traditional Balinese could never have published the observations in this book,” its appearance could be open to new forms of discussion. The graceful flow of Diana Darling’s translation (from the original French) is a remarkable achievement.

Converting hours of transcribed conversations into an organized text is no easy task, and Buvelot has designed chapter headings and introductions as signposts, making the reader’s journey through the material more manageable. A consistent glossary of terminology and references would be even more helpful, as the text is often cluttered with redundant footnotes, along with definitions of terms that could be more efficiently collated in one place. Both text editing and proofreading seem to have been neglected in the production process; these could both be improved in a subsequent edition. The interviews published here appear to have been completed prior to the emergence of COVID-19, suggesting that pandemic-related impacts and changes in Bali still require further interpretation. It is hoped that these two interlocutors will not end their in-depth explorations of what it means to be Balinese and observe Bali at the 50-year mark. You have a lot more to consider and share with us.

Eric Buvelot, Bali, 50 Years of Change: A Conversation with Jean Couteau. Trans. Diana Darling, Brisbane: Glass House Books, 2022.

For international orders and the e-book version, please visit the publisher website. The book is also available from Amazon.

Maria Zurbuchen wrote The language of Balinese shadow theaterwas a representative for the Ford Foundation in Indonesia and currently works as a consultant and translator from her home in California.

Comments are closed.