Vikram Sampath’s brutal attacks were not academic activism. It was the opposite of restraint

TThe bizarre spectacle, which began with a controversial plagiarism allegation against famed historian and high-profile intellectual Vikram Sampath, played out on social media and courtrooms in India last week. The saga turned into a farce when one of the accusers started waving a list of potential backers that turned out to be filled fake names.

The sad episode that gripped the academic communities of India and the United States made me reflect on the events of the past fortnight – a time that could have been very different and done far less damage to their entire cast.

As a practicing academic surgeon with a calling from a prestigious medical school in the United States, my mission is to provide world-class medical care and expand the horizons of my specialty through research and teaching. My colleagues and I publish in peer-reviewed journals, edit book projects, and often give oral academic presentations.

Occasionally we are asked to make oral presentations at a conference, and organizers may require that we submit a transcript of a speech to be published in a compendium at a conference – often referred to as the “proceedings” of the conference. Because these “proceedings” are not always peer-reviewed – meaning they are rigorously reviewed with robust criticism – the submissions tend to be more informal than other submissions.

So what would I do if I read one of these procedures attributed to a colleague who looks fairly familiar? What if I put that colleague’s work into plagiarism detection software and found that my colleague actually paraphrased my work accurately and even reproduced lines? What if the colleague inserted appropriate citations and full references in some places in the text, but made some mistakes in locating some citations after each paraphrased passage?

What if this colleague had published five well-received books at hundreds of thousands of words and many other peer-reviewed publications, but the overlooked citation problem was found in just one non-peer-reviewed journal? What if that colleague is otherwise a rigorous, exemplary scholar with no record of similar errors?

Academic ethics would compel me to turn to the colleague, even if I don’t know him, and inform him that he has not quoted or quoted these passages and ask for corrections. If the colleague ignores my request, my next step would be to contact the journal and ask for corrections to the submission. Otherwise, only then can I escalate the matter and inform the institutions associated with that person to investigate.

But that’s not how it went for Vikram Sampath.

Also read: Savarkar would not have found a place in today’s politics: historian Vikram Sampath

How Sampath was targeted

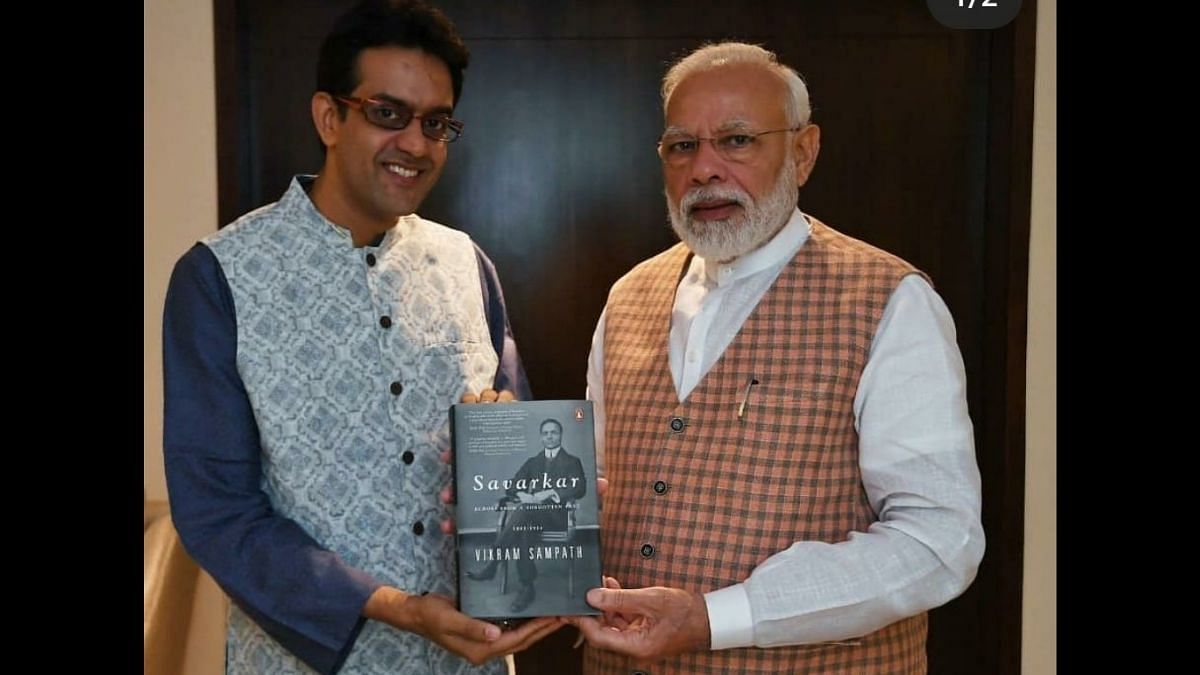

The template I illustrated above was not the one followed by his accusers – the three academics at US institutions. Instead, Sampath came under scrutiny at every appearance because some fellow historians disapproved of the subject matter of Sampath’s best-selling biography, The Story of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. Lesser known among Indian nationalist leaders who opposed British colonial rule, Savarkar was imprisoned in a remote penal colony and tortured, though he wrote prolifically in support of independence. Savarkar, an atheist, propagated anti-colonial ideas along with a notion of “Hinduness” or Hindutva, which is now seen in the ideology asserted by India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

Ananya Chakravarti of Georgetown University, Audrey Truschke of Rutgers University, and Rohit Chopra of Santa Clara University, a non-historian who teaches communications, decided to subject the corpus of Sampath’s work to Turnitin software, which is an author’s work compared to other previously published work. To do that, they would have had to copy and paste all of Sampath’s books into the software. It is to be noted that apart from a single paraphrased paragraph in one of the books, no other significant errors were discovered.

The trio’s next course of action was likely to be to search online manuscripts written by Sampath and subject them to the software. As Sampath says, a single article — a transcript of a speech delivered at the India Foundation in 2017 that was later submitted for a non-peer-reviewed Proceedings publication — was reportedly expected to have citation errors. The work of two American professors, Vinayak Chaturvedi and Janaki Bakhle, has been cited in the references and in several places in the five-page essay, but some passages paraphrased from Bakhale’s work have been identified as missing citations or quotation marks, as per convention prescribes.

But has the academic triad reached out to Sampath and helpfully suggested that he be changed, while the vast majority of his work has been beyond reproach, have a few errors been discovered in a single passage in what is likely a long-forgotten speech transcript? No. Instead, the three wrote a letter to the Royal Historical Society, a UK-based honorary society of historians-scholars, which granted Sampath membership for his scholarly achievements. The three co-authors contended that Sampath’s error in this article was similar to that of their “tepid undergraduate students‘ and a ‘plunder’ so severe that Sampath should be expelled outright from society.

Also read: Plagiarism, data manipulation harm India’s research, government body sounds the alarm

A career end punishment

To be dismissed from membership in an honor society, something like a scholarship to the Royal College of Surgeons in my view, would be an unthinkable setback. Truschke, Chopra, and Chakravarti thus called for a sanction akin to an end-of-career punishment, although there is no evidence that Sampath’s work shows a pattern of similar errors.

In fact, nothing the accusatory trio did has come to light through discreet private communications, as academics normally correspond. The very first act of this saga was an audience “Release” of the letter on Twitter from a contributing author to Al Jazeera.

Once on social media, thousands responded to a spate of posts challenging and defending Sampath. Faced with an unsavory trial by Twitter and an open attempt to destroy his career through a direct appeal to the society to which he had just been elected, Sampath turned to Indian courts. Sampath successfully obtained an injunction barring Twitter in India from making the harmful allegations against him.

A few days later, Truschke tweeted a list of alleged supporters of her cohort’s anti-Sampath adventurism. The list, which mostly included the academicians’ own colleagues at Georgetown and Rutgers, apparently included famous historians and columnists like Ramachandra Guha and Pratap Bhanu Mehta, and even high-ranking political leaders. Within hours, this spectacle became comical as many of these “signers” denied their association with the list and reported that their names had been forged without permission.

But the real damage has been done. Sampath’s name now had the prefix “plagiarism accusation” and Truschke flattered that his Wikipedia had written a “new entry on the charges” almost in real time.

Why did Chakraborti, Truschke, and Chopra act against Sampath with such malice? Why did they seek the equivalent of the historian’s “capital penalty”?

Also read: Who is Savarkar? And should we discuss it? 14-state survey delivers amazing results

A History of “Scholar Activism”

The academics are no strangers to what they call “scholar activism” and controversy. All three accusers have long histories of adamantly denying the existence of Hinduphobia and clashing with Hindu American groups they label “right-wing” or “Hidutva.” Sampath was targeted for his apparent “sin” in writing a widely acclaimed tale about Savarkar, whom the three activists believed to be the true source of this Hindutva ideology.

Chakraborti and Chopra were among the co-sponsors or speakers at an activist-focused online gathering targeting the Desmantle Global Hindutva (DGH). This meeting caused international outrage as it was attended by several academics who insisted that Hindutva could not be “dismantled” without dismantling Hinduism, the religious tradition. These attacks on Hindutva were seen as a ploy by many Hindu Americans to imply that they had “dual allegiance” and default support for India’s ruling party – the BJP.

Truschke is already facing a libel suit for conspiracy to defame the Hindu American Foundation (HAF) by falsely alleging that the foundation is sending funds to India to support “slow genocide” or “sponsor hatred.” (Disclosure: I am co-founder of HAF). And Chopra recently made headlines when Twitter summarily suspended his India Explained Twitter account after posting a controversial tweet about Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Truschke and Chakraborti even published a “field manual” that purported to warn against “Hindutva harassment” but actually spread bizarre Hinduphobia, such as banning “elite Hinducentric” ideas held by Hindu students on campus . Truschke’s recent release of a graphic accusing an organization of Hindu students on campus, the Hindu Students Council, of promoting Hindutva led to loudly Rebuffing college students who insisted that the “Hindutva” charge was a common gaslighting tactic to silence the voices of American Hindus.

It’s certainly okay for academics to invest in activism, and my work with HAF certainly demonstrates my own commitment to advocacy. But when this activism focuses on their own scholarly domain—as we often see in South Asian studies—it is critical for these activists to remove ideological blinkers, disclose their conflicts of interest, and avoid a narrow-minded overreaction to a scholar who may not follow an ideological line.

Challenging the integrity of a colleague is a serious charge. When a colleague has no record of misconduct, additional restraint is required. Playing off personal or ideological grievances through malicious tweets or public letters to historical societies, arming a charge of plagiarism, is the opposite of restraint.

Sampath’s brutal academic targeting just shouldn’t have happened that way.

When science is politicized and dissent is ostracized, academic integrity is the biggest loser.

Aseem Shukla, MD, is Professor of Surgery (Urology) at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine and co-founder of the Hindu American Foundation. Views are personal. He can be reached at @aseemrshukla

Comments are closed.