The winds promise bad omens

RELEASED on October 02, 2022

Karachi:

As a former international breaking news editor, I have a penchant for novels set in newsrooms. There’s Evelyn Waughs scoop, a scathingly funny satire challenging Fleet Street; Michael Frays Towards the end of the morningwhich focuses on the people responsible for the thankless task of putting together a newspaper’s boring mishmash, Annalena McAfee’s the spoiler, which follows two very different kinds of women – a war correspondent and a famous gossip editor – in newspapers just before the dot-com boom, and Tom Rachman’s grandiose debut The Imperfectionists, which portrays the people who make up a fictional international newspaper.

What each of these novels gets right are the astute descriptions of newsroom culture: the inflated egos of the staff, the way the pressures and clinical decision-making continue to shape their personalities, how the bleakness of the job translates to great moments of humor. But it’s the universality of any high-pressure environment that makes a newsroom such a perfect place to shoot a novel about the human condition: almost everyone can understand the hysteria and excitement of realizing there’s only ten minutes to go to press that the 80-point heading reads “public” instead of “public”. Add that to the people responsible for spreading information about the world, their unique personality traits and you should have a recipe for success.

Iqbal worked as a journalist both in India and in the Gulf – the book is mainly set in editorial offices. In the prologue there is a promise of what kind of book this might be – Abbas is the newsroom editor, he has perfected the art of censorship: “He knew exactly how to bury the unsavory stories about the sheikhs – their tribal struggles, indifference and Cruelty to foreign workers, their sickening and eccentric heights of luxury – and how to blow up stories that weren’t newsworthy in any newspaper anywhere in the world. He knew the importance of stories on page two, of visits to cooks and magicians or music bands, or of overrated paintings by wealthy expatriate housewives. More importantly, he knew how to focus more on world news to cover up local stories of human rights abuses.”

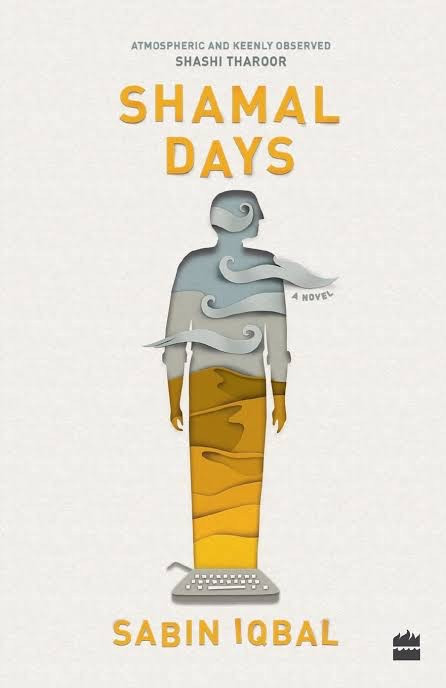

This is exactly the kind of insider knowledge, gossip and gossip about editorial culture and how it leads to burnout, disaffected workers and an immigrant population deeply concerned with its role in the world. That’s why it’s such a surprise that Sabin Iqbals Shamal days, about Abbas, a middle-aged narrator turned proofreader-editor in an unnamed Gulf desert country – a novel that has everything a recipe for success should need – is so lackluster. Despite some brilliant moments throughout the book, Shamal Days is a somber read, too meandering for readers to make much of its central premise about alienation and the immigrant experience.

The book is narrated largely from the narrow third-person perspective of Abbas, a Malaysian expatriate who got his start as a proofreader in an international newsroom. Abba’s personality can be aptly summed up as overwhelmingly insecure, extremely horny and desperately unhappy. Abbas is a miserable character, holding on to his perspective is an exercise in suffering – Abbas is unable to understand his own agency. As a character, he thinks things only happen to him. This can be tolerable in a shorter book, or perhaps a book that’s more plot-driven or less cluttered with unnecessary supporting characters. In Shamal Days, which unfortunately suffers from all of these things, it’s the book’s fatal flaw: Iqbal chooses to jump back and forth in time to explain the story of Abbas. It’s unclear why the book is set up that way, the narrative sometimes jumps to characters that have never been introduced while simultaneously transporting the reader to a time they’ve never been to. Sometimes this leads to delightful surprises, like that of a World Cup hopeful, Abdullah, whose story is told so beautifully it could have come out of another novel entirely. At other times we will simply leave the mainstream of Abbas’ narrative to wander down a tangent. The reason for the tangent will never manifest to the reader, sometimes it will happen so much later in the book and after so many other tangents that the meaning will have been lost. This is where the sense of a muscle being tensed to impress someone who will never quite see it arises. The bottom line is this: Iqbal often leaves a thread open and begins a small but somewhat enticing puzzle for the reader. As a result of these tangents, this narrative mystery is abandoned, the reader is distracted with characters and other unnecessary information. By the time the narrative puzzle is solved, the reader may no longer care about the outcome.

All of this added up to make Abbas one of the least likable male characters I’ve read in recent memory. Going back to its dour narrative, reorienting myself to the thin plot, and moving forward was tiring. A far too long prologue at the beginning hinted that Abbas would make a choice. I assumed we would watch Abbas grapple with that decision or the consequences of that decision. This doesn’t happen. Instead, we are treated to a book about an indecisive man who spends most of his life not realizing that not making a decision is actually a decision in and of itself. It is unclear whether Iqbal is aware of this and whether we need to understand that Abbas is aware of this.

In any case – whether or not Abbas learns to become decisive feels undeserved. Because we switch perspectives to so many other characters, almost exclusively men, and all of those men tend to describe women in such callous and physical ways, I never quite understood if all of the men in this book were deeply misogynistic, or if Iqbal was the misogynist. I’m not usually the kind of reader who thinks the characters in the book represent the author’s point of view, but this book never made women anything but sexual objects while granting men all sorts of shades of characterization. It’s hard to believe that towards the end of the book, after almost 200 pages of seeing women as the objects or recipients of his insatiable sexual desire, Abbas would have any kind of human revelation.

The writing in Shamal Days is uneven at best. There are paragraphs that are headed and distract from the actual novel. Sometimes the prose is simply repetitive and not masterful enough for the reader to tell if this is unintentional. But there are moments when the writing is clear and concise, and incredibly perceptive in pointing out that everyone in this novel lives in a nation built on the backs of an imported working class. This is something I have not seen before in English language fiction. Job seekers are described as “looking at each other as best they could in a walk-in boxing match, completely in the dark about each other’s strengths and weaknesses,” while “petite Filipinas and frail Sri Lankan housemaids hung around phone booths like fiddy ants, waiting for theirs to be the one.” It’s also one of the few places where Abbas really works as a character – his affect and general despair are the right lens to illuminate his observations for the city around him. Every time Abbas encounters someone from the working class, he notes their ethnicity and home country, making sure to add a swipe so the reader knows his role in the machine that makes the country work.

Abbas tells the reader that the shamanic winds come with a lingering sense of bad omen, and perhaps this is the feeling the book is intended to evoke in the reader, instead the book primarily left that reader with a sense of unfulfilled promise.

Mariya Karimjee is a freelance writer. All information and facts provided are the sole responsibility of the author.

Comments are closed.